Indoor air pollution from gas stoves: the latest research

A growing body of research links indoor air pollution with asthma, heart disease, and some cancers. This article take a comprehensive look at the health impacts that a gas stove can have.

Indoor air pollution has long been known to be a cause of a wide variety of health issues. Mold can trigger allergies, radon is linked with lung cancer 1, and cleaning products can release volatile chemicals that trigger respiratory problems such as asthma 2.

While secondhand smoke, radon leaks, and cleaning products might be relatively well known as sources of indoor air pollution, there’s growing awareness of the impact of gas stoves on air quality. A collection of recent research shows that gas stoves can release hazardous chemicals including nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, and benzene with serious consequences: as many as 1 in 8 cases of childhood asthma might be traceable to pollution from gas stoves.

That’s one reason why some homeowners are switching from gas to induction stoves. Not only can induction stoves offer a superior cooking experience, but they eliminate indoor pollution related to gas leaks and combustion.

However, not all cooking-related indoor air pollution can be eliminated by switching to electricity. The gas industry, predictably, has also pushed back on this research.

Because this issue is important to your health and a big reason why many homeowners are making the switch to all-electric homes, I thought that it would be worth summarizing the latest research.

Indoor air pollution: what we do know

Indoor air pollution is a massive global problem: the Global Burden of Disease Study, a collaboration of over 3,600 researchers from around the world, estimates that indoor air pollution is responsible for at least 2.3 million deaths around the world. The World Health Organization places that number higher at 3.8 million globally.

Of all the indoor pollutants, fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is the greatest concern. In its global assessment of the issue 3, the WHO states that:

While a number of air pollutants are associated with significant excess mortality or morbidity, including NOx, ozone, carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxides in particular, PM2.5 is the air pollutant that has been most closely studied and is most commonly used as proxy indicator of exposure to air pollution more generally.

PM2.5 refers to particulates smaller than 2.5 microns (μm) in size. The WHO adds that these are damaging because they can penetrate deep into the lungs and are associated with lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, and respiratory infections.

Cooking is the major source of PM2.5 in indoor air pollution and is a particular problem in developing countries where solid fuels are commonly burned in cooking stoves, including wood, dung, crop waste, charcoal, and coal.

However, PM2.5 pollution from cooking is also a problem in wealthier nations where electric, propane, and natural gas ranges are most common. This is because particulates are released by the cooking process itself, and not just the combustion of cooking fuel. Because of this, particulates will be produced even when cooking with a conventional electric or induction cooktop. However, while burning propane or natural gas is much cleaner than cooking with dung or wood, studies have shown that a plethora of pollution is still produced.

Particulates can be produced by gas or electric cooking

Cooking food using high heat methods, such as grilling, frying, and sautéeing, can produce air emissions regardless of the type of stove used. This includes PM2.5 and other chemicals such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Burnt or charred foods will contain these chemicals, and these cooking methods will also produce air emissions. Anyone who has cooked a steak indoors will be familiar with the smoke that can quickly fill a kitchen.

According to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, PAHs are a possible carcinogen that have been linked with a higher risk of some cancers, but a conclusive link has not yet been proven 4. However, the health risk of particulates like PM2.5 is much more clear, making them something to avoid.

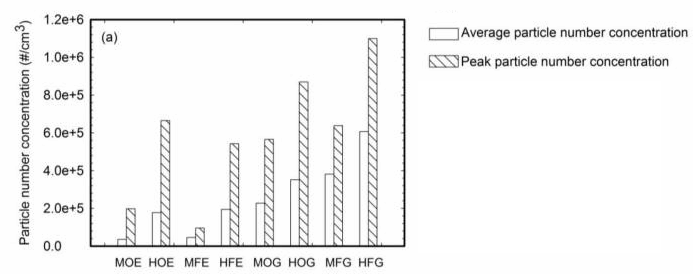

Particulates can be produced even with an electric range, so switching from gas to electric won’t eliminate the risk. However, one study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health showed that cooking at high heat on a gas stove produced roughly twice as much particulates as cooking on an electric stove, and roughly three times as much when cooking at medium heat compared to an electric stove. The study noted that the advantage of electric cooking was maintained whether a ventilation hood was used or not. 5. This means that a gas stove can be responsible for a significant amount of particulates, even before accounting for emissions from the cooking process itself.

The takeaway is that you should always use a kitchen hood that vents outside when cooking, especially when cooking at high heat or using a gas range.

Gas stoves produce benzene, a known carcinogen

Benzene (C₆H₆) is a chemical that is classified as a known carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the U.S. National Toxicology Program, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and has been linked to leukemia and lymphomas 6. It’s one of the byproducts when you burn methane – the main component in natural gas. Theoretically, burning methane should only produce water and carbon dioxide, but the combustion that happens with your cooktop is imperfect, causing pollutants like carbon monoxide and benzene.

A recent study published in Environmental Science & Technology that was conducted in 87 homes showed that the use of gas stoves often raised the concentration of benzene in the air above health guidelines. In 29% of cases, using a single gas burner on high or setting the oven to 350°F raised the concentration of benzene in the kitchen to a level comparable to second hand tobacco smoke 7.

The study further noted that the benzene concentration can rise above health guidelines even when kitchen ventilation is used, possibly because not all kitchen hoods provide good ventilation or actually exhaust outside.

Finally, the study tested whether benzene could be produced by the cooking process itself, similar to how cooking at high heat can produce particulates, or due to unburned gas leaking into the air. The authors showed that cooking food does not produce benzene, and while unburned natural gas can contain some benzene, the amount is small relative to the benzene produced by combustion.

Natural gas leaks and a rebuttal by the gas industry

The study by Kashtan et al. described above provides an important follow up to an earlier study published in the same publication by Lebel et al. 8. In the latter, the authors collected 185 natural gas samples from homes in California and then modelled the impact of leaky gas stoves on indoor air quality. They concluded that gas stoves can leak enough natural gas, even when turned off, to raise the benzene concentration in homes to a level comparable to second hand tobacco smoke.

This study received quite a bit of media attention and drew a response from the American Gas Association. In their rebuttal, the AGA stated that natural gas only contains trace amounts of pollutants, and that the assumptions in their modelling would result in unhealthy indoor air only under implausible scenarios. Their main critique is that the study used modelling rather than actual measurements to draw its conclusions 9.

However, yet another study took real measurements from 53 homes with gas stoves in California and found that all stoves leaked gas to some degree, even when turned off 10. The authors further noted that the stoves leaked gas at a rate approximately 4.5 times higher when turned on, indicating that not all of the gas is ignited by the burner flame. They found that this is a particular problem with gas ovens, which cycle on and off to maintain the set temperature, allowing unburned gas to escape with every cycle. Although this study addresses the main critique in the AGA’s rebuttal of Lebel et al., as far as I know the AGA has made no mention of it.

In total, the authors estimate that about 1% of natural gas usage by stoves can be attributed to leaks. While this may seem small, they estimate that the climate change impact of all of the methane leaked annually by gas stoves in the United States is comparable to the carbon dioxide emitted by 500,000 cars. (Methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.)

The study also measured nitrogen oxide emissions (the chemical responsible for smog) and concluded that in homes that don’t use kitchen ventilation, the indoor air can exceed EPA standards for NOx within just a few minutes of turning the stove on.

Link between childhood asthma and gas stoves

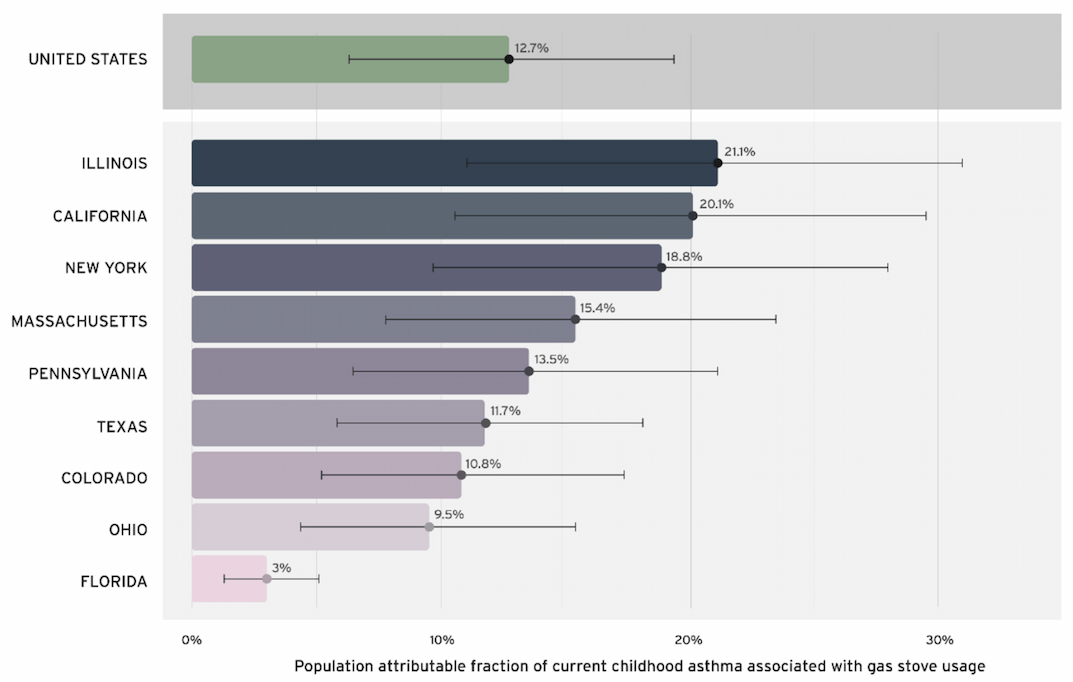

A study published in 2022 reviewed the data from 27 previous studies and concluded that as much as 12.7% of childhood asthma cases in the United States can be traced back to pollution from a gas stove in the home 11. The numbers vary by state due to the different types of fuel in common use in each state. For example, in Florida where many homes are all-electric, only about 3% of childhood asthma cases can be traced back to a gas stove in the home. However, that number rises to 18% or higher in New York, California, and Illinois where gas hookups are much more prevalent.

The black bars in the graph indicate the range of uncertainty, so the data indicates that the true number could actually be around 30% in California and Illinois.

Indoor air pollution is a particular concern for infants

One point made in the AGA critique of the research is that only “trace” amounts of pollutants might be attributable to leaky stoves (which again ignores pollution due to the operation of the stove). However, even trace amounts can be dangerous to vulnerable populations such as pregnant women and infants. Health Canada points out the correlation between NO₂ exposure and negative health effects on asthmatics (especially children) and adults with COPD, and also states that the possible adverse effect of long-term exposure warrants setting the guideline for permissible NO₂ levels in a home at a relatively low level 12.

A study in the journal Epidemiology also warns about the hazards of cooking with natural gas in homes with pregnant women and infants due to the sensitivity of developing brains to environmental hazards, stating: “Because maturation of the brain cortex is intensive in the first few years of life, this period of neurodevelopment may be particularly vulnerable to environmental pollutants." 13. They agree with the conclusion drawn by previous studies and warn of the dangers of particulate pollution to young children: “Ultrafine particles and compounds absorbed by them (eg, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and metals) may traverse the blood–brain barrier and cause neuroinflammation, lipid peroxidation, and other damage directly in the brain.”.

Bottom line: always use ventilation when cooking, but switching away from gas cooking could be a good idea

Indoor air pollution is unquestionably a public health hazard, especially for vulnerable people such as infants and those with asthma and heart conditions, and there is a growing collection of research that points to gas stoves as being a notable health risk.

On the surface, natural gas appears to be a clean fuel: when you light your gas stove, it doesn’t produce smoke (at least it shouldn’t!), and is certainly cleaner compared to the solid cooking fuels used in the developing world. However, burning natural gas does produce harmful byproducts that aren’t always apparent. These include the pollutants mentioned above such as PM2.5 and benzene that pose a clear risk to health, but also others that I haven’t even mentioned yet including formaldehyde and sulfur dioxide.

It’s worth noting that there are other sources of indoor air pollution such as cleaning products and offgassing from furniture and other household products. In addition, cooking with any type of stove at high heat, including electric, will produce smoke and fine particulates. For these reasons, good ventilation should be used any time you cook, and air quality monitors can be useful to let you know when your air quality starts to deteriorate for any reason.

However, if you’re debating whether to switch out your gas stove for a conventional electric or induction model, improved air quality and health is a big reason to make the change. Gas stoves can pollute your air even when off, and when operating they emit far more pollution than an electric model. Plus, induction stoves have other advantages including better safety features and cooking performance.

Finally, methane (the main component of natural gas) is a potent contributor to climate change. If you’re concerned about the environment both inside and outside your home, that can be another reason to switch to an induction stove.

References

Radon and Cancer (American Cancer Society) https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/radiation-exposure/radon.html ↩︎

Cleaning Supplies and Household Chemicals (American Lung Association) https://www.lung.org/clean-air/indoor-air/indoor-air-pollutants/cleaning-supplies-household-chem ↩︎

Ambient air pollution: a global assessment of exposure and burden of disease [PDF] (World Health Organization) https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/250141/9789241511353-eng.pdf ↩︎

Burnt Food and Carcinogens: What You Need to Know (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) https://blog.dana-farber.org/insight/2019/09/does-burnt-food-cause-cancer/ ↩︎

Measurement of Ultrafine Particles and Other Air Pollutants Emitted by Cooking Activities (International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2872333/ ↩︎

Benzene and Cancer Risk (American Cancer Society) https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/chemicals/benzene.html ↩︎

Gas and Propane Combustion from Stoves Emits Benzene and Increases Indoor Air Pollution (Environmental Science & Technology) https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.2c09289 ↩︎

Composition, Emissions, and Air Quality Impacts of Hazardous Air Pollutants in Unburned Natural Gas from Residential Stoves in California (Environmental Science & Technology) https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.2c02581 ↩︎

Review and Comments “Composition, Emissions, and Air Quality Impacts of Hazardous Air Pollutants in Unburned Natural Gas from Residential Stoves in California” (American Gas Association) https://www.aga.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/american-gas-association-review-and-comments-lebel-et.-al-october-2022-10.26.22-1.pdf ↩︎

Methane and NOx Emissions from Natural Gas Stoves, Cooktops, and Ovens in Residential Homes (Environmental Science & Technology) https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.1c04707 ↩︎

Population Attributable Fraction of Gas Stoves and Childhood Asthma in the United States (International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health) https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/1/75 ↩︎

Residential Indoor Air Quality Guideline: Nitrogen Dioxide (Health Canada) https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/residential-indoor-air-quality-guideline-nitrogen-dioxide.html ↩︎

Indoor Air Pollution From Gas Cooking and Infant Neurodevelopment (Epidemiology) https://journals.lww.com/epidem/fulltext/2012/01000/indoor_air_pollution_from_gas_cooking_and_infant.5.aspx ↩︎