10 ways to reduce your bills in an all-electric home

Retrofitting your home to be either partially or fully electric can save you money overall, but you still might be bothered by your larger electric bill. Here are some tips to reduce your electricity usage.

Switching your home away from fossil fuels to electric appliances can reduce your overall utility costs. By switching from, say, a gas furnace to a heat pump or trading in your gasoline car for an EV, your total energy costs can drop due to the higher efficiency of electric alternatives.

However, once you’ve made the switch, you’ll have an electricity bill that’s much higher than before. Even though you’ll be saving money by making your natural gas or gasoline pump bills go down, you might be bothered by seeing a bigger electric bill every month. In a way, this is a good thing, because all of your energy costs will be consolidated into one place, making it easier to see your total consumption.

If you find yourself in this situation, the 10 tips below can help reduce electricity usage in your home. Many of these tips can be used by any home, not just all-electric ones.

Get an energy audit (which are often free)

One of the best places to start is to get an energy audit of your home. They are often offered discounted or free by utility companies, so check with yours to see what’s available. There are also state agencies, such as Energize Delaware, Energize Connecticut, and NYSERDA in New York that offer home energy assessments for free or a reduced rate.

There is also a federal tax credit worth up to 30% of costs, to maximum of $150. It’s the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit 1, and includes credits for a wide range of improvements including insulation and heat pumps. (More about those later.)

According to Home Advisor, an energy audit can normally cost between $208 and $700. If you can’t get one for free, an energy audit can cost as little as $75 through one of these programs.

What happens with an energy audit? A professional will visit your home and perform a room-by-room assessment to identify opportunities for you to make efficiency upgrades. They may use an infrared camera to assess the insulation in your walls and ceilings, use a blower door to identify air leaks, check the combustion in your gas furnace, identify humidity issues, find phantom energy loads, and more.

Especially if you can get one for free, there’s no reason to not do it. In my experience, the process takes less than an hour. In exchange, you’ll have a more informed picture of where energy is being used so that you can focus on upgrades that have the highest return on investment. This is a lot better than making home energy improvements in a less systematic way, and will usually recoup whatever small cost you paid for the audit.

One special type of energy analysis is called a Manual J calculation, and should be used by an HVAC company to calculate the cooling and heating that your home needs. If a company doesn’t do this analysis, they will instead be using a rule-of-thumb method to size the heat pump for your home, which will often result in equipment that is oversized for your needs, reducing the efficiency of the system.

Selectively insulate and air seal your home

If your home uses a heat pump, heating and cooling will be one of the biggest electricity consumers in your house. There are a few strategies you can use to reduce this cost, but the best place to start is to minimize that amount of work that the heat pump needs to do in the first place. That means upgrading your insulation and eliminating air leaks.

Making a home well-insulated is easiest when it’s constructed, but it’s possible to add insulation to an existing home as well. The cost and feasibility will depend on where you’re adding it.

- Blown-in attic insulation is often the easiest upgrade, and can be done as a DIY project if you have a friend to help. If you have an unconditioned attic with inadequate insulation, this is one of the easiest upgrades you can make that has a high return. 16 inches of loose-fill cellulose insulation will add an R-value of 56 to your attic, which will be sufficient for any climate zone in the United States if you already have some existing insulation 2.

- Blown-in wall insulation is more complex, so you’ll want a contractor for this work. Cellulose insulation is also an excellent choice here, and if the insulation is densely-packed it will also double as an effective barrier against air leaks. It can often be added on top of some types of existing insulation too.

- External wall insulation is an excellent product that should be considered for any new build. For retrofits, it probably mostly makes sense to add it only if you need to upgrade the siding of your home. External wall insulation is a rigid foam board that is attached on the outside of your home, underneath the siding. The great advantage of external insulation is that it covers any gaps in the interior insulation, such as heat traveling through the vertical wood studs of the wall.

Air leaks can also be a big a contributor to heat loss. Identifying leaks can be hard, and the biggest ones often aren’t doors and windows as you might think. Instead, the rim joist (where the outer wall meets the foundation) and attic leaks are often the biggest sources of leaking air in a typical home. Finding these leaks is best done with the help of an energy audit, especially when a blower door is used.

Bottom line? If there’s a biggest bang for buck, it is probably fixing any rim joist and attic air leaks, which can often by done with a can or two of expanding foam insulation you can purchase at a hardware store. After that, adding insulation to an under-insulated attic probably has the next largest return on investment.

What often doesn’t have a good return on investment is replacement windows. They are often touted as an energy saver, and it’s true that a good double- or triple-glazed window will outperform an old single-pane window. But they’re expensive, and the energy savings is rarely high enough to pay back the cost. Unless they’re badly damaged, replacing your windows purely to save energy usually won’t result in a financial payback.

Another big savings bonus is that insulation is eligible for a federal tax credit of 30%, up to a maximum of $1,200.

Operating your blinds can have a surprisingly large impact

You know how baking hot it can get in a parked car in the summer when the windows are rolled up? There’s a lot of heat energy in the sun’s rays, and that’s something you can take advantage of to heat your home in the winter or minimize the air conditioning you need in the summer.

The way to do this is to simply operate your blinds to either maximize or minimize solar heat gain. It might not seem obvious that this is useful in the winter when the air is cold, but the sun’s rays carry just as much energy in the winter as they do in the summer.

This heat energy is called solar heat gain, and calculating it accurately involves a lot physics. The tools used by professionals 3 are too involved for a casual homeowner to bother with. However, we don’t need that kind of accuracy to prove the point we’re discussing. For the novice, the calculator on the Sustainable By Design website 4 serves perfectly well to make a rough estimate of how much heat energy you can stand to gain in the winter or avoid in the summer by shading your windows.

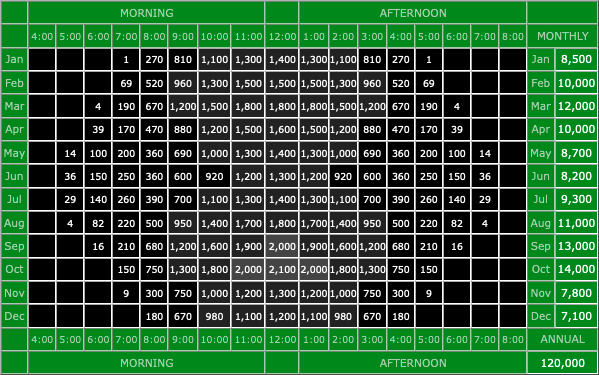

To use the calculator, enter your location and the type of windows you have, or the solar heat gain coefficent (SHGC) specification of the window if you happen to know it, and the units you prefer (kW or BTUs). You’ll get a table of data like this:

Each cell in the table is the total amount of heat energy you can expect to receive per area of south-facing window by hour for each month, with the last column representing the total amount of heat energy for each month. In my example, for the 12 o’clock hour in the month of January, I can expect to receive approximately a total 1,400 BTUs of heat energy through each square foot of window (I specified clear double-glazed), or 8,500 BTUs per month.

I measured one window in my south-facing office, and each is about 9 square feet. There’s three windows for a total of 27 square feet. That means in an average January I can receive 229,500 BTUs of heat energy for free if I keep my blinds wide open during the day.

How much heat is that? A small space heater uses about 1,500 watts, which is 1.5 kWh if you operate it for one hour. One kWh of electricity converts to 5,100 BTUs, which means to generate 229,500 BTUs of heat I would need to operate that space heater for 30 hours. That’s a lot of electricity, so getting that heat for free instead is a big bonus.

It’s similar when you want to keep your home cool. In August, those windows will receive 11,000 BTUs per square foot per day, or a total of 297,000 BTUs per day in my office. A small window unit air conditioner is rated for about 8,000 BTUs per hour, which means it would need 37 hours to remove all of that heat energy. Again, that’s a lot of electricity.

The real picture is a little more complicated than this, especially if you have insulating cellular shades. Keeping cellular shades closed will reduce heat loss in winter, so the net heat gain by keeping your shades open in winter will be less than this compared to keep the shades closed. However, the R-value of cellular shades is typically overstated because they need side seals to be truly effective 5.

Take advantage of passive cooling and heating

The concept described above - letting the sun warm your home when you need heat and shading it when you want it to stay cool - is an aspect of passive solar. (This is in contrast with active solar that uses photovoltaic panels to generate electricity.)

Passive solar is a deep topic, but the basic concept is to use building design and landscaping to regulate the amount of solar heating that a building receives. Many elements of passive solar design need to be incorporated from the start, such as the direction the building is oriented. For an existing home the options are more limited, but there are effective steps a homeowner can take, such as adding awnings that shade your home in the summer but are retracted in the winter to let the sun in. Deciduous trees around your home can perform a similar function because they drop their leaves in the winter, allowing sunlight to warm the building, while their leaves in the summer provide shading.

In some climates, it is possible to build a “passive house” (aka. Passivehaus) that does not use any mechanical heating or cooling at all 6.

Passive houses require maximum energy efficiency and use of passive solar, but more modest measures can be taken by the average homeowner. For a starting point, you can read the NREL’s article on Passive Solar Technology Basics 7.

Use energy monitors to know what your big electricity hogs are

A common tip for saving energy is to avoid so-called “phantom” energy loads, which are electronics that continue to draw electricity even when apparently switched off. This is often due to standby modes that allow electronics to turn on more quickly.

While phantom loads can be significant, they are less of a problem with newer electronics that have an “eco” mode that reduce this electricity draw. To find out the impact that your electronics have, you can purchase a cheap energy meter. An example is the Kill-a-Watt which sells for about $30. Simply plug the Kill-a-Watt into a power socket, then plug your appliance into the Kill-a-Watt. It’ll give you an instantaneous reading of how many watts the appliance is using.

If you take a tally around your house, you might find that all of your electronics are drawing perhaps a couple dozen watts or less. For example, a PlayStation 5 will reportedly draw 1.3 watts of electricity when off.

In contrast, a central air conditioner or heat pump will draw a couple thousand watts or more when operating. This is not to say that you shouldn’t worry about phantom loads. However, if you want the most energy savings, you should focus on the biggest loads first.

A little plug-in energy meter won’t let you measure the energy usage of your heat pump, range, or other major appliances. Instead, you’ll need a whole-house energy monitor. These include products by Sense and Emporia that connect to your electric panel and let you see on an app everything in your home that is using electricity.

At the most expensive end, you can get a “smart” electrical panel that not only reports how much electricity each appliance in your home is using, but lets you switch them off and on from an app. This makes it easier to take advantage of cheaper off-peak utility rates.

Look into time-of-use rates with your utility

Most electricity utilities have time-of-use (TOU) rates where the price of electricity varies during the day. TOU rates encourage utility customers to shift their electricity usage to hours when the electric grid is under less load.

Cheapest off-peak rates are typically at night, although in places with a high percentage of solar power, such as California, off-peak times may extend into late afternoon due to abundant solar energy in the middle of the day.

Some utilities offer a choice of TOU rates, including rates aimed at EV drivers. For example, I switched from National Grid’s fixed electricity rate to a TOU rate for EV drivers, and saved about $370 in the first year. Off-peak rates are often substantially lower than peak rates. For example, Southern California Edison’s off-peak rate in winter is 62% less expensive than on-peak.

Preheat and precool your home if you have TOU

If you have a TOU rate, you’ll want to shift as much electricity use onto off-peak hours as possible. If you have a heat pump or central air conditioner, this is easy to do by precooling or preheating your home before peak hours begin.

Simply set your thermostat to make your home a few degrees warmer or cooler before on-peak hours begin. This will let your home “coast” on the temperature adjustment and minimize the amount of energy you use during peak hours.

For example, if your on-peak hours are between 4 p.m. and 9 p.m. as they are with many California utilities, in the summer you could set your thermostat to be 3 or 4°F colder starting around 2 p.m., set it to a couple degrees higher starting at 4 p.m., and then resume your normal temperature at 9 p.m.

Depending on the level of insulation and thermal mass in your home, that extra cooling might keep your home at a comfortable temperature without needing air conditioning until 9 p.m. You’ll have to experiment with the settings because every home will respond to temperature changes differently, but once you have it dialed in, you can reduce your heating and cooling bills without having to make any modifications to your home.

Use a smart or programmable thermostat

Taking advantage of a TOU electricity rate is a lot easier if you have a smart or programmable thermostat, but they’re also useful for any homeowner who wants to operate their heating and cooling systems more efficiently.

A programmable thermostat will let you set different temperatures at different hours of the day. A smart thermostat can do the same and adds other features such as Wi-Fi access so you can change the temperature while you’re out of the house, occupancy sensors that can reduce the heating or cooling when nobody is home, and automatic temperature setting based on your typical pattern of being home and away.

Smart thermostats, such as the Ecobee and Nest, can also automatically preheat and precool your home according to your TOU plan. This is often better than managing it manually, because the thermostat will automatically learn over time how quickly your home returns to its previous temperature.

Make sure ducts are sized correctly and filters are clean

If you have central air or heating, an under-the-radar source of electricity usage is the blower motor. It’s essentially a powerful fan that pushes air through your home’s ducts that can use a few hundred watts of electricity when running.

A forced air system consists of distribution ducts that send conditioned air throughout the home, and return ducts that pull air from different rooms into your furnace or central heat pump. The surface area of all those ducts produces a lot of friction, which places a load on the blower motor.

If the ducts are sized too small or have unnecessary bends, the friction will increase, placing additional load on the blower motor, increasing the electricity use. A dirty air filter will do the same.

As a homeowner, you can minimize the electricity use by making sure that your air filter is changed regularly. If you are installing a new furnace, central air conditioner, or heat pump, ask the HVAC company to verify the correct duct size for your system and to look out for problems such as excessive bends or usage of flexible ducts.

Don’t vent heat pump hot water heaters outside

Heat pump hot water heaters are a relatively new product in North America. Instead of using natural gas or an electric coil to create hot water, they use a small heat pump. (They’re often called hybrid hot water heaters because they will fall back to the electric resistance coil when the heat pump can’t generate enough heat on its own.)

Heat pump hot water heaters pull air from the surrounding room, extract heat from it to create hot water, and expel cold air back into the room. These heaters can be installed with ducts so that this exchange happens with outdoor air instead.

This can be advantageous in warm climates where the outdoor air can be much warmer than air conditioned indoor air, especially in the summer. By pulling in warmer air from the outdoors, the heat pump will operate more efficiently and use less electricity.

However, in both hot and cold climates, it will typically make more sense to install a heat pump hot water indoors without ducting to the outside.

In the summer when you might need air conditioning, the heat pump will give you some cold air for “free”. It will take air from the surrounding room, extract heat that is dumped into the hot water tank, and blow cold air back into the room. That’s a bonus that will lessen the load on your central air conditioner.

However, this is a disadvantage in cold climates because your heating system will need to make up for the heat used to generate your hot water. If you use a central heat pump for home heating, it means two heat pumps are involved: the hot water heater uses a heat pump to generate hot water, and then your central heat pump needs to make up for the lost heat energy that the water tank extracted from the air. There are efficiency losses at both steps, so hybrid hot water heaters operate at a disadvantage in the winter months.

However, you wouldn’t want a ducted system in a cold climate. This is because cold winter air will make a hybrid hot water heater operate at a much lower efficiency, and perhaps require the unit to fall back to electric resistance heating.